“I was trying to understand how images travel between people, how they move through time, and if there was a way to use writing and picture making to figure out more about how images work.” (Barry, 2014, p. 49)

“Sometimes things that seem to have been forgotten for a long time are actually conserved quite close to us” (Serres, 1995, p. 55)

Figure 1. Carrot peeler hands. One hand holds a carrot while the other hand runs a peeler along the carrot skin, removing the outer layer. Lines extending from the forearms turn into fronds matching the shape of the greens at the top of the carrot. (original illustration)

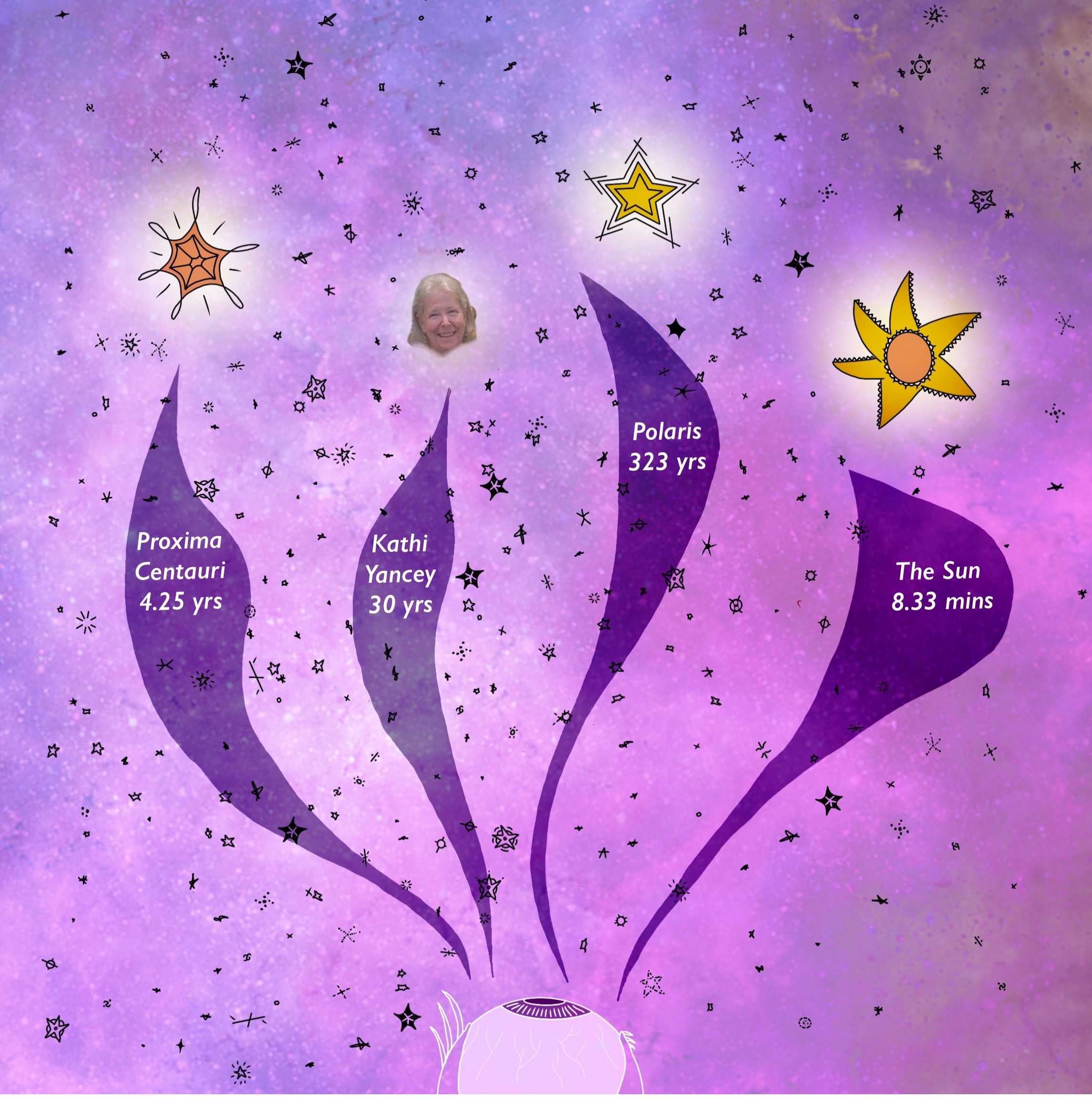

To open a nebulous segment on visuality, “V is for Visual,” is to presuppose an amateur stargazer’s awe upon looking up at the night sky neither impeded by cloud cover nor by cityglow: upsky is vast! Go on; look up. Pause. Space junk and a growing number of blinkering atmospheric interlopers notwithstanding, the stars are the stars, and their celestial light reaches across inconceivable distances. Though they famously command ever-renewed wonder, stars may be casualized as similar, or as skewing toward sameness. They do not, after all, turn in EZPass receipts on the distances their photons have travelled. For that, we defer to astronomers whose instrument-assisted formulations provide good enough estimates. Polaris, or the North Star, is 323 light years away, so on any given night, the light we observe set off 323 years ago (Stein, 2022). Proxima Centauri, the star nearest to our sun, sends light expressed from 4.25 light years away (The Imagine Team, n.d.). Earth’s Sun, eight minutes and 20 seconds. And here we are now because Kathleen Yancey retired in 2023, after an illustrious and still-shining 30-year career.

Figure 2. Stargaze. A singular eyeball gazes toward four figures (Proxima Centauri, 4.25 years; Kathi Yancey, 30 years; Polaris, 323 years; and The Sun, 8.33 minutes), each annotated with an identifying label and timespan. (original illustration)

Like the others in this abcdeary collection, a 2023 interview with Kathleen Yancey by Stephen McElroy occasioned this piece. In the interview, Yancey described a marked shift in her imagination that occurred in the late 2000s at a time when she sought to augment alphabetic thinking and become a more visual thinker. She credited three motivating factors for this shift. First, when working with Clemson University architecture undergraduates on their professionalizing portfolios, their integration of coordinated visual elements frequently led to complications. Yancey learned from those students that it was neither seamless nor automatic for them to select and incorporate iconographic components that would later contribute to visual cohesion across the genre set. Crediting Diana George’s 2002 article, “From Analysis to Design: Visual Communication in the Teaching of Writing,” Yancey reiterated during this portion of the interview a concern that the field of rhetoric and composition, as well as many who identify visual rhetoric as a scholarly interest, has proven far more committed to the analysis and critique of visual artifacts than to the design or creation of them. Second, she attributes her shifted mindset to the scholarship by people like Richard Lanham whose book, The Electronic Word (1995), emphasized for those composing with the digital interface the continuous oscillation between looking at and looking through. Yancey described how at/through bistability opened possibilities for visual rhetorics and proved helpful in multimodal compositions of her own. Third, and finally, Yancey described about her writing process the increasing significance of slides for the generative alternation between exploratory visual communication and the accompanying manuscripts crafted to express closely related ideas. An entanglement of slides and scripted presentations was not only a practical consideration; it also animated an interplay among rhetorical genres and heightened awareness of audiences and, in some situations, their implicit expectations for an ornate orchestration tuned simultaneously to the images and the text.

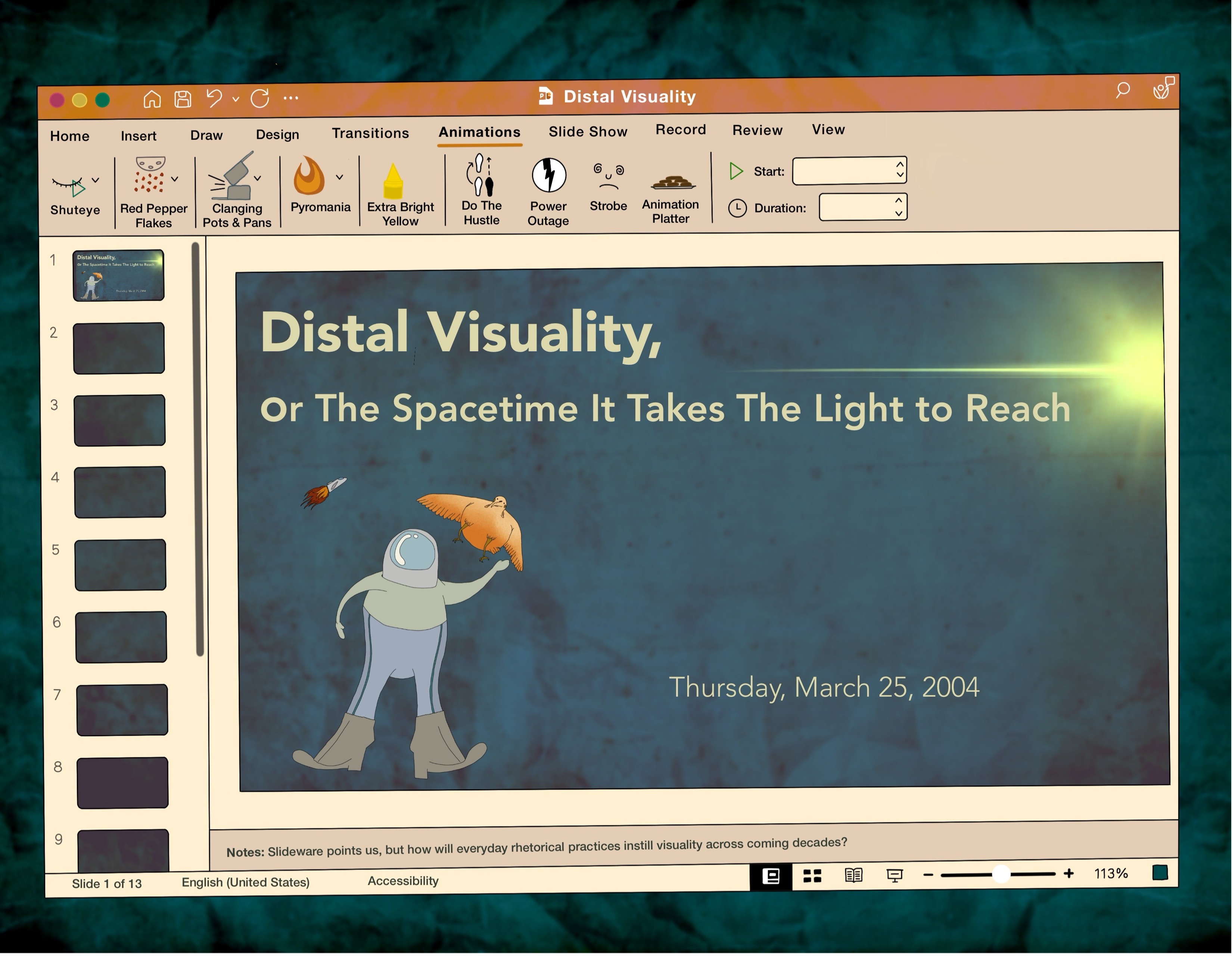

All three premises are relatable; they elicit a confirmatory sense of yes, this was true for me, as well, albeit in later times and elsewhere places. With the first point, in teaching contexts, I, too, learned that everyday visual rhetorics, even for the few self-identified visual thinkers who showed up in writing classes, was unbeholden to any shared or predictable baseline; that visual rhetorics, perhaps for its heavy reliance upon theories and methods adapted from visual studies more than practices and techniques from applied arts starkly favored analyzing and interpreting images more often than making them. And with the third point, slideware, once disentangled from the all too frequently odious and unimaginative stock of quick, ready-made templates (or oftentimes worse, clipart), invited exploratory and playful investigations of visual arrangement and sequencing. Slideware relieved of built-in party poppers and overwrought pizzazz effects opened possibilities for compositional exploration among visual and textual elements—and although this shift wasn’t quite on level with the launch of the graphical user interface in the mid-1990s, with slideware multimodal composing was more fully afoot.

Figure 3. Slideware points us. In this parody of Microsoft Powerpoint, the software’s default menu bar has been recreated to feature playful variations on slideware animations and effects. Among the buttons are “Clanging Pots & Pans” and “Do the Hustle.” The focal slide presents the title, “Distal Visuality, or The Spacetime It Takes The Light to Reach,” and includes the date, “Thursday, March 25, 2004.” A distant rocket flies above and beyond a figure in a space suit along with a Cinnamon Queen chicken. (original illustration)

Granting that all three points from the 2023 interview elicit assent and invite extension, I frame them as inventional influences for what will now turn key to V-for-visual lock–please open!–with further elaboration on the second premise, the prepositional, because it lends to a concept I wish to develop hereafter: distal visuality. Distal visuality amplifies an image’s spatiotemporal vectors owing to even more prepositions than Yancey referenced, citing Lanham, and with simultaneous consideration of deixis, or space-time pointing words, such as here and there, or now and then, which Yancey invoked and extended in her 2004 CCCC keynote address, “Made Not Only in Words.” Writing as if by starlight, then, as an occasional stargazer more than as an astronomer, in what follows I will attempt to establish an aperture—and to loft a luminary—for the concept of distal visuality. I am following as one would a will-o'-the-wisp the concept of distal visuality because it may aid us in attending to visual artifacts as entimed, but entimed in ways that relate to our own turbulent entimedness, leading us well beyond the more commonplace temporal considerations of fourth dimensions in visual studies, such as motion, animation, or linear sequentiality. Distal visuality suggests a spatiotemporal phenomenology of seeing drawn to peripheries, surrounds, and beyonds—distant edges both in time and in space. Distal connotes “outer reaches” and “away from the center,” a zone beyond focus yet relationally accessible. Distal visuality finds form and light in the iridescent vapors at the fringes, summoning us to witness that which is not focal. If looking at also means not to look at something else, rather than surrendering these something elses to the inobservable, or occluded, distal visuality sends sightlines to the darting and fleeting edges, expressing not so fast to all that glimpses by or that lingers in that zone.

As an eyes-refreshed phenomenology of seeing—and of making things to be seen, distal visuality activates deixis and prepositions, refracting visual composition to wider and weirder apertures of possibility. Like the letterform V, distal visuality dots sightlines well beyond conventional limits, fixing a fulcrum whose vectors simultaneously span time and space, while overrunning the ocular in service of the imaginary. Distal visuality amplifies, as would high color saturation, the pointer-like qualities of deixis, and the relational traversals of prepositions, offering acts of visual composing (interpretive, constructive, and inventional) an evermore concerned for all that we cannot possibly be looking at when we are looking at anything else.

If you have held on until now, I have a hunch you are ready for an example. So I will pose one exemplar and then explore its theoretical significance, with the goal of linking distal visuality more thickly to deixis and to prepositions.

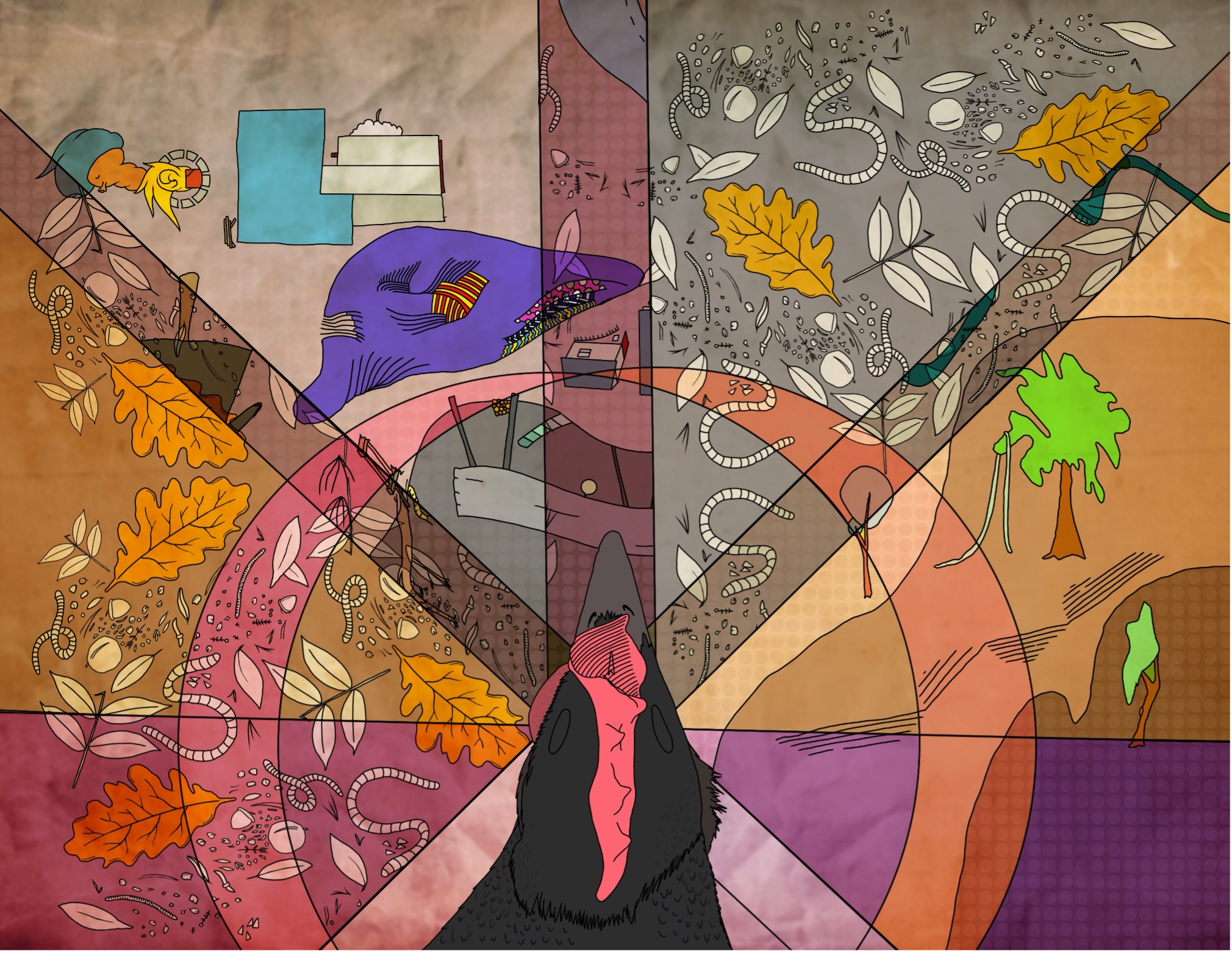

Brilliant are the ocular powers possessed by chickens (gallus gallus). Like many birds, reptiles, and freshwater fish, chickens are tetrachromatic, which means they have a fourth color receptor, making it possible for them to see a greater variety of colors than humans can see (Goldsmith, 2006). They have a third eyelid called a nictating membrane, which glides horizontally, while protecting and lubricating the eye; this is especially effective for keeping airborne irritants at bay, as when dust bathing (Kathy the Chicken Chick, 2013). A chicken’s two eyes together constitute 50% of a its cranial volume; whereas the comparable measure for humans is just 5% of cranial volume (Wisely et al., 2018). Like many other birds, chickens also have dual foveas, which allow them to see with sharp precision activity to the side and, combinatorially, out in front, for a bifocal view (Waldvogel, 1990). Additionally, according to several online forums and veterinary websites (Petrik, 2012; Thames, 2018), chickens develop in each eye more keenly calibrated near- and far-sighted capacities, and they manage this throughout the 21-day incubation phase, while inside the eggshell, as the embryonic chick shifts so that one eye is toward light and the other eye is away from light.

Figure 4. Chicken-eyed view. The overhead view of a chicken’s head appears in the lower center area of the image, suggesting its perspective, which looks onto a multicolor field divided by lines. The different sections of the visual field alternate between zoomed in and zoomed out scales, rendering an impression of what a bifoveal view might look like. (original illustration)

Chickens, thus, are exemplars of distal visuality because of the in-built bifocal condition. For them, a parallax view is readily available, and with this, they have the capacity to see at once near and far, to integrate here and there, which is also a lot like merging then and now—or converging here and there, then and now to their narrowest and most knotted junctures.

On the morning of Thursday, March 25, 2004, in the theater of the Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center in San Antonio, Texas, Kathi Yancey delivered the CCCC Chairs’ address, “Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key.” In it, citing Leu, et al.’s work on new literacies, she emphasized deixis as a “defining quality” of digital literacies because they are, in effect, hyper-, traversing here and there, bridging then and now. The following year, in a Computers and Composition Online article, “Weblogs as Deictic Systems,” Collin Brooke extended deixis to the serial, transitory compositions circulating across blogging platforms, and especially to the social, rhetorical networks sponsored thereby whose ties connect times, places, and people. In their well-known article on rhetorical velocity, “Composing for Recomposition,” Jim Ridolfo and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss, too, gestured to deicity, or “the now and then of texts,” underscoring deixis again as a persistent characteristic of rhetorical delivery and digital circulation.

The deixis I ascribe to distal visuality owes much to perching on these shoulders of giants, as the saying goes. From the scholarly cast, distal’s yonder enfolds concerns for the hyper-; for the networked, multiply oriented referentiality of digital writing; and for the darting delivery routes giving rise to variable rhetorical velocities. But that is not all. Distal visuality requires continuous and renewed consideration of the attention structures extended across these pointed-toward depths.

Writing about distinctions between deep and hyper attention, N. Katherine Hayles documents device-dependent shifts, which amount to rising media consumption and a decline in sustained reading. She goes on to note, crediting the observations of director Alexander Singer, that film-viewing audiences in the 1960s required as long as twenty seconds to process an image, but by the early 2000s, filmmakers accepted as commonplace a much faster clip, in that audiences needed only 2-3 seconds to process an image (Hayles, 2007). I understand this shortened glimpse clock to suggest not that audiences were becoming vastly more comprehensive and quick in their ocular processing, but instead that looking at blinkered ascendant and the surrounds—the deep surrounds, or the distal, faded: time’s abbreviation is visuality’s curtailment, too.

So while the onset of the hyper is unsurprising, the chicken, with her dual foveas, wide field of vision, rapid ocular processing rate, bouquet of tetrachromatic hues, and evolutionary adaptations for simultaneous near and far-sighted acuity may, if we are receptive to something like ornitho-gogy, tutor humans about how much our peripheral vision does not notice. As exemplars of distal visuality, chickens count as but one of the many possible “generative oddkin” Donna Haraway theorizes in Staying with the Trouble (2016). Granted, some contemporary critics, such as Alan Jacobs, are not as encouraged by the extreme cases where we find science fictional interspecies leaps suggested as enduring inroads to elongated temporal bandwidth and personal density. Jacobs remains committed nevertheless to a project, in Breaking Bread with the Dead (2020), that wanders with genuine, unflinching curiosity toward, rather than arbitrarily limiting, the Big Here and the Long Now—a phrase he credits to musician Brian Eno. I include it here because it resembles what distal visuality pursues: when availing ourselves, as visualists (seers and makers of things to be seen) of antecedents in the surround, this phenomenology of seeing opens maximally to spatiotemporal extremities: beyonds, minutiae, and fantastic voyages. With deixis, or multiply pointered terms entrusted to feathered exemplars, the bird’s-eye view consummated for distal visuality is better lit than before—more big dipper than little dipper. Where do we journey when the flock leads the shepherd? Generative oddkin invite us again to rehome Lanham’s at/through bistability with expanded cast of prepositional possibilities.

This distal visuality invites a refreshed pairing for deixis and prepositions. As Kathi Yancey reminded us, prepositions have, at times, shined light on matters of interest to those engaged in the areas of computers and writing, digital media, and writing pedagogy. Lanham’s at-through oscillation theorized the continuous, mutually informing perceptual toggles for digital rhetorics and for the personal computer interface, knowable as a discrete, temporarily isolable object of analysis in its own right (at) and also as a viewport overlay, or lens, for filtering subsequent perceptions (through). More than a decade later, in Lingua Fracta (2009), his award-winning reinvention of classical rhetoric for digital environments, Collin Brooke extended the set of special prepositions with the addition of from. Establishing as salient the context of the end-user, from emphasized the person-at-the-interface as one who is specifically situated, embodied, entimed, emplaced, attention-giving, and suspended between subjectivity and collectivity. Later, in my own writing on worknets, or the iterative, webbed, network maps created to trace ties interwoven throughout the secondary sources commonly associated with written academic research (2015), I tried to expand the set of prepositions to include along and across. In service of worknets, along paired with exploratory, or destination unknown inquiry, and across aligned with itinerate, telos-directed pursuits—those with a known, foreseeable goal, or end.

Only very recently did I learn of Michel Serres’ translated interviews, in which he details his eclectic interests—a wandering curiosity, an idiosyncratic inquiry paradigm, and a correspondingly poetic style—as attributable to a theory of prepositions: “So I wander. I let myself be led by fluctuations. I follow the relations and will soon regroup them, just as language regroups them via prepositions” (p. 102). For Serres, while subjects (“substantives”) and verbs tend to drive traditional philosophy, prepositions operate quietly as reagents for relations. With a deserved nod to “generative oddkin,” I think again about the chicken’s ways of seeing when Serres says he thinks “vectorially,” going on to note that “[i]t’s better to paint a sort of fluctuating picture of relations and rapports—like the percolating basin of a glacial river, unceasingly changing its bed and showing an admirable network of forks, some of which freeze or silt up, while others open up—or like a cloud of angels that passes, or the list of prepositions, or the dance of flames” (p. 105). Distal visuality would, with deixis and an expanded array of prepositions as cooperating possible attunements, feather out relations felt and non-obvious, eddied in time, and beyond the communicable edges of verbal language. Might this revitalize contemporary visual rhetorics from its bogged down repetition of analysis?

Figure 5. Orchard of prepositions. Presented as an aerial view of an orchard, the illustration shows the tops of several trees lining a V-shaped pathway. Inside the V’s stem are twenty-three prepositions drawn into the tree trunks throughout the orchard. Six chickens are free-ranging in the orchard. (original illustration)

Above and beyond at, through, from, along, and across, these prepositions, a part of speech Serres suggests “has almost all meaning and has almost none” (p. 106), are easy to list and easy to take for granted: until, con (spa., with), within, alrededor (around), among, por (spa., by), near, for, beiderseits (ger., on both sides). They are not acting neatly or singularly in their pathing of relations, but they are distinctive and formidable, particularly when construed as eye drops for a refreshed phenomenology of seeing, and a check-in about how visual rhetorics belong (or fail to belong) in the contemporary field, whatever the field. Recalling Hayles’ mention of briefer and briefer glimpses sufficing in film, contemporary visual rhetorical practices—whether reading and analyzing images or creating them—are prone to what Jenny Odell (2019) calls “context collapse,” the diminishment of contextual anchors in the endless streams of digital information proliferated by hyperculture, generally, and especially characteristic of social media platforms. When successive images are queued indefinitely (think Instagram, Flickr, Facebook, TikTok, Pinterest, Dribble, Tumblr, We Heart It, etc.), context falters and is prone to all out collapse. When context collapse runs amok, a feature and not a bug of digital communications nowadays, what distal visuality recalls instead is a vectored crosshatch—a relational tapestry (multiply prepositioned), slowed but nevertheless circulating, situated deictically, and, therefore, chancing context accretion, an ethical, reparative quality we need with greater urgency, not only for visual rhetorics, but for multisensory rhetorics and for multimodality, broadly construed. With deixis and prepositions, distal visuality for visual rhetorics beckons return for the faraway and long gone, the night sky and the light sent across it. Contextualism, too, with its vaster, pluralistic noticings, coalesces these antecedents in the surround—an aid to distal visuality, as well as a positive, recuperative implication to follow from it.

The nearest I have come to attempting distal visuality project is found in Radiant Figures: Visual Rhetorics in Everyday Administrative Contexts (2021), a collection I co-edited and also contributed to, along with Rachel Gramer and Logan Bearden. A prime exigence for Radiant Figures was our noticing (and empirically verifying) just how limitedly visual rhetorics appeared to be playing a part in the lifeworlds of writing program administrators, if judged on the basis of published WPA scholarship and the archives of WPA: Writing Program Administration. Yet, we knew the generative, suasive effects of visual artifacts in our experiences and also understood these visual rhetorical practices to be a crucial part of work by many of our colleagues. Thus, the collection invited visual rhetorical practices and related artifacts into the light—and, thereby, implicitly revalued the shadows where such practices and related artifacts dwelt.

Additional areas have expressed a comparable need for engagements of visual rhetoric. In the Conclusion to their book, On African-American Rhetoric (2018), Keith Gilyard and Adam Banks underscore one such possible project, writing, “We mention Vine and meme culture to highlight the serious need for significant work in African-American visual rhetorics, from our current moment back throughout all periods of Black life in this society. We have no book-length formal study of African-American visual rhetorics, and such a project is way overdue” (p. 125). “From our current moment,” now, and “back throughout,” then, suggests congruencies with what I have illustrated here as distal visuality.

To conclude, I will collage into place as if held by masking tape a personal example and offer further context for the “carrot peeler hands” illustration that bookends this piece. “Carrot peeler hands” lends form to distal visuality, to a phenomenology of seeing that occurs when, while peeling carrots at the kitchen sink for a soup or a stir fry, I see these hands as my mother’s hands, my great-grandmothers’ hands, and too the hands of their mothers, longer ago, matrilineal parallax, of a certain food preparing sort. Not long ago, while visiting Michigan in November, on a mid-late Saturday morning, I’d just peeled two pounds of carrots for a slow cooker evening meal, and at the same time served my four-year-old granddaughter, Victoria (Tori), two eggs, over easy. I didn’t mention to her, and never have, the carrot peeler hands matrix—only scratched her back lightly and asked if she was happy with the eggs, to which she responded, the way a distal visualist would and without turning her head, “I can see it.”

Figure 6. Carrot peeler hands, recontextualized. Figure 6 matches Figure 1, except in this case, the carrot, peeler, ribbon of peeled skin, hands, forearms, and fronds perform distal visuality, expressing a kind of palinopsis, or visual echo, suggestive of the author’s hands while preparing vegetables for a stew, but also the hands of all who have held carrots over a sink, peeling them, and making a meal for others. (original illustration)

Barry, L. (2014). Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor (Illustrated edition). Drawn and Quarterly.

Brooke, C. G. (2009). Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media. Hampton Press.

Brooke, C. G. (2005, Fall). Weblogs as Deictic Systems. Computers and Composition Online. http://cconlinejournal.org/brooke/index.html

Chick®, K., The Chicken. (2013, May 9). Chicken Anatomy: Nictitating Membrane, The Eyes Have it. The Chicken Chick®. https://the-chicken-chick.com/chicken-anatomy-nictitating-membrane/

DeVoss, J. R. and D. N. (2009, January 15). Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery [Text]. 13.2; Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy. https://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/velocity.html

George, D. (2002). From Analysis to Design: Visual Communication in the Teaching of Writing. College Composition and Communication, 54(1), 11–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/1512100

Gilyard, K., & Banks, A. (2018). On African-American Rhetoric (1st ed.). Routledge. https://www.amazon.com/African-American-Rhetoric-Keith-Gilyard/dp/1138090441

Goldsmith, T. H. (2006). What Birds See. Scientific American, 295(1), 68–75.

Gramer, R., Bearden, L., & Mueller, D. (2021). Radiant Figures: Visual Rhetorics in Everyday Administrative Contexts. Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press. https://ccdigitalpress.org/radiant-figures

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press Books.

Hayles, N. K. (2007). Hyper and Deep Attention: The Generational Divide in Cognitive Modes. Profession, 187–199.

Jacobs, A. (2020). Breaking Bread with the Dead: A Reader’s Guide to a More Tranquil Mind. Penguin Press.

Lanham, R. A. (1995). The Electronic Word: Democracy, Technology, and the Arts. University of Chicago Press.

Mueller, D. (2015). Mapping the Resourcefulness of Sources: A Worknet Pedagogy. Composition Forum, 32. https://compositionforum.com/issue/32/mapping.php

Odell, J. (2019). How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Melville House.

Petrik, M. (2012, March 31). Chicken Vision. Mikethechickenvet. https://mikethechickenvet.wordpress.com/2012/03/30/chicken-vision/

Serres, M. (1995). Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time: Michel Serres with Bruno Latour (R. Lapidus, Trans.). University of Michigan Press.

Stein, V. (2022, January 24). Polaris: How to find the North Star. Space.Com. https://www.space.com/15567-north-star-polaris.html

Thames, K. (2018, August 16). The Eyes Have It, Chicken Eyes That Is. – Thames Veterinary and Farm. https://thamesfarm.com/2018/08/16/the-eyes-have-it-chicken-eyes-that-is/

The Imagine Team. (n.d.). The Nearest Neighbor Star. Retrieved January 10, 2024, from https://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/features/cosmic/nearest_star_info.html

Waldvogel, J. A. (1990). The Bird’s Eye View. American Scientist, 78(4), 342–353.

Wisely, C. E., Sayed, J. A., Tamez, H., Zelinka, C., Abdel-Rahman, M. H., Fischer, A. J., & Cebulla, C. M. (2017). The chick eye in vision research: An excellent model for the study of ocular disease. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 61, 72–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.06.004

Yancey, K. B. (2004). Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key. College Composition and Communication, 56(2), 297–328. https://doi.org/10.2307/4140651