Kathi Yancey’s work has impacted each of us, over time, in different ways and formats and media, and in different contexts. Each of us has also dedicated scholarly and pedagogical work to and around delivery and to rethinking, revising, and remixing delivery for our contemporary, digital world. We were approached and invited to write a chapter focused on D for delivery and on Kathi’s contributions to our thinking in rhetoric and writing studies about delivery, a task we were keen to take on.

Two days after receiving the initial invitation from Stephen, Matt, and Rory, Dànielle reached out to them and to Doug and Naomi:

I would just like to report that I had a dream last night that Naomi, Doug, and I were writing postcards to one another about Kathi's work and then we created digital versions of the postcards as part of this amazing project about delivery across analogue and digital spaces inspired by the arc of Kathi's work.

I am not kidding.

#nerddreams

Stephen, Matt, and Rory shared with us the 30-minute interview with Kathi focused on delivery. We met to discuss how we might approach delivery and to honor Kathi’s contributions given the expansiveness of both her body of scholarship and the myriad ideas, challenges, and questions that emerged in the interview. As we each watched the interview and read the transcripts and reflected on our experiences with Kathi and with Kathi’s work, we found ourselves gravitating toward postcards.

In "Evocative Objects: Reflections on Teaching, Learning, and Living in Between," authored with Doug Hesse and Nancy Sommers, Kathi wonders about how Americans “composed in the twentieth century," especially in ways that aren't recognized or haven't been curated, protected, collected, and preserved. In this discussion, she includes an image of a black postcard (see Figure 1) as representative of these sorts of uncurated, not typically protected, not owned, sometimes collected but not often preserved in collections of everyday writing.

Figure 1: Postcard from Hesse, Sommers, and Yancey (2012, p. 348).

Each of us were captivated by this type of writing and by this particular means of production and, important to this chapter, the means of delivery of this type of writing. We decided to honor Kathi’s attention to postcards and write each other two postcards. We talked about recording and photographing ourselves writing, and reflecting on the process of interacting with the postcards and with each other via postcards. We talked about anticipating and reading each others’ postcards, from our separate distances. We talked about reading each others’ postcards to and with each other after we received them and as we met via Zoom to work on the chapter.

In this webtext, we share our postcards, via narration, via analysis, via video, and via writing. We focus first on themes that emerged as we wrote and shared our first postcards—themes of embodiment, of the analog and the digital, and of the genre and genre-ic work of postcards, then on themes that more specifically emerged in Kathi’s interview on the topic of delivery: on everyday texts and actions; on writing and democracy; on violence, grief, and community composing and mobilization. We conclude by sharing an additional found postcard and by reflecting across our postcards and our postcard writing. We also reflect, as best we can and as much as possible in one short chapter, on the exceptional contributions Kathi has offered us in her scholarship, especially her work on delivery.

As the video above illustrates, each of us has found our way to and with Kathi’s work in different contexts and with different purposes, needs, and questions. In this brief review of Kathi’s work, we home in on her contributions to our discipline’s—and our own—contemporary thinking about delivery.

Yancey’s attention has long been focused on the expansiveness of writing and composing and on the many, many things we create, write, and circulate. At her Chair’s Address at the 2004 Conference on College Composition and Communication, Yancey stood at the podium, a laptop to her right, to her left, and directly in front of her. She orchestrated photos, quotes, captions, and more between the laptops and across the two display screens as she delivered her address. In the December 2004 issue of College Composition and Communication, Yancey likewise made the most of the modalities at hand. The print article featured images, text call-outs and sidebars. She proclaimed “never before has the proliferation of writings outside the academy so counterpointed the compositions inside” and described literacy as being “in the midst of a tectonic change,” many of those changes happening beyond our classrooms and many of them emerging across digital spaces (p. 298). Yancey’s scholarship has created through-lines in rhetoric and writing studies, posed questions that remain as relevant today as they were when she first raised them, and engaged composition across all the spaces and places where composing happens.

We would argue that “Made Not Only in Words” contains some of Yancey’s most compelling, most provocative claims and questions about delivery. She asked

Suppose I said that basically writing is interfacing? What does that add to our definition of writing? What about the circulation of writing, and the relationship of writing to the various modes of delivery? (p. 299)

Early on in the piece, she also says “we have a moment.” The moment in which she delivered this address and then wrote this piece was in the early 2000s. And what a moment this was! The World Wide Web was on a rebound and in the midst of a massive transition and evolution after the collapse of the initial imagined web economy of the late 1990s. We were in the midst of a file-sharing revolution and on the very cusp of social media. YouTube didn’t yet exist; the first tweet hadn’t yet been sent (and wouldn’t be sent until March 2006). Email had been anchored as a communication norm and truly a revolutionary one for those of us who did our work via postal mail and fax years previous. As Yancey articulated, this moment was one where writing proliferated in and with and across emerging technologies and digital places and spaces. Our concepts of audience evolved with digital writing platforms and our understandings of networked spaces of delivery. Yancey called attention to the writing publics of a rapidly changing 19th century Britain and the writing publics of a rapidly changing 21st century United States, pointing out the reading and writing happening outside of school contexts and focusing on the technologically mediated writing communities of today.

In the “third quartet” of the essay, Yancey posed a set of pedagogical claims about circulation that invoke delivery. Specifically, she argued that the field of composition hadn't effectively addressed delivery, and that instructors might do so by asking writing students to “consider what the best medium and the best delivery for such a communication might be and then create and share those different communication pieces in those different media, to different audiences” (p. 311). We would argue, more than 20 years since the publication of this incredibly important piece, that many of us are still working to (or, honestly, working to not) extend invitations to students in our writing classes to robustly consider media and delivery.

In "Evocative Objects: Reflections on Teaching, Learning, and Living in Between," authored with Doug Hesse and Nancy Sommers, Yancey focused on another, more specific, moment: The April 18, 1906 earthquake in California. Her discussion homed in on invention and the inventive practices of presenting earthquake-related data. She read images and data renderings as relational, as surfacing relationships: "geologically, the plates and continents; compositionally, the page, the screen, the interface, the network" (p. 343). She looked AT and THROUGH the images, exploring who produced the images and who owns the images. Later in the essay, she turned to another focus, wondering about "how other Americans composed in the twentieth century," especially in ways that aren't recognized or haven't been curated, protected, collected, and preserved. In this discussion, she includes but does not directly discuss a postcard (see Figure 1 in the introduction to this chapter).

It’s impossible for us to read this piece and—although the word “delivery” does not appear once in the essay—not see it as an essay about delivery and the inseparability of invention and delivery.

While delivery is often at the foreground in Yancey’s work, postcards are often on the writerly table, peeking out from between books on the shelf, or sitting adjacent to and in illumination of key themes across her work. For instance, in her 2015, "Cultures, Contexts, Images, and Texts: Materials for a New Age of Meaning-Making"—the print version of her 2013 address at the South Atlantic Modern Language Association—Yancey described circulation "at the heart of our new digital postcard archive... this archive currently hosts thousands of postcards: one can view them in any number of ways and can learn about each one" (p. 9) in ways resonant with history, archiving, and public memory (see McElroy, 2017).

Yancey described collecting postcards in her introduction to a special issue of South Atlantic Review on "Everyday Writing" and articulated our deep connections to everyday writing. She shared that her sisters (typically uninterested in her scholarly work) were very interested in her postcard collecting and

wanted to know what texts people were writing... about how composers learned to write new genres—like postcards in the late nineteenth century and blogs in the late twentieth—when there was no school instruction. (p. 1)

In an essay in the special issue, Yancey described a special topics course she taught on everyday writing, with postcards as a genre explored alongside letters, notebooks, signs, zines, and other seemingly mundane forms of writing.

In the introduction to Delivering College Composition, Yancey explored what it means when we link college and composition and delivery. Here she expansively situated delivery (in this context as a powerful metaphorical tool) to include the layout and design of the physical classrooms in which we teach writing/deliver writing instruction and the bodies/people who deliver such teaching.

This expansive focus, to us, is illustrative of a thread across Kathi’s work, a thread that pulls across the analog and the digital in rich, provocative, compelling ways (see also, Yancey, 2016). Indeed, we hope to have paid homage to this thread of Kathi’s work with our approach to this chapter, and the ways in which we wrote physical postcards and digitally shaped the claims we’re making here.

In writing our first postcards, mailing our first postcards to one another, receiving and spending time with each others’ postcards, we found three compelling delivery-related threads emerge, all of which resonate with Yancey’s work on delivery: the embodied dimensions of composing; the ways in which we think, write, work, and encounter across the analog and the digital; and the genre conventions of postcards and how those conventions shaped (or disrupted) our work with the postcards.

Everyday writing is a material practice, one inflected by the technology of a time and by its economics as well. (Yancey, 2020b, p. 168; concluding comments to special issue of “Everyday Writing”).

As the video above illustrates, we of course brought each of our bodies to the act of writing the postcards.

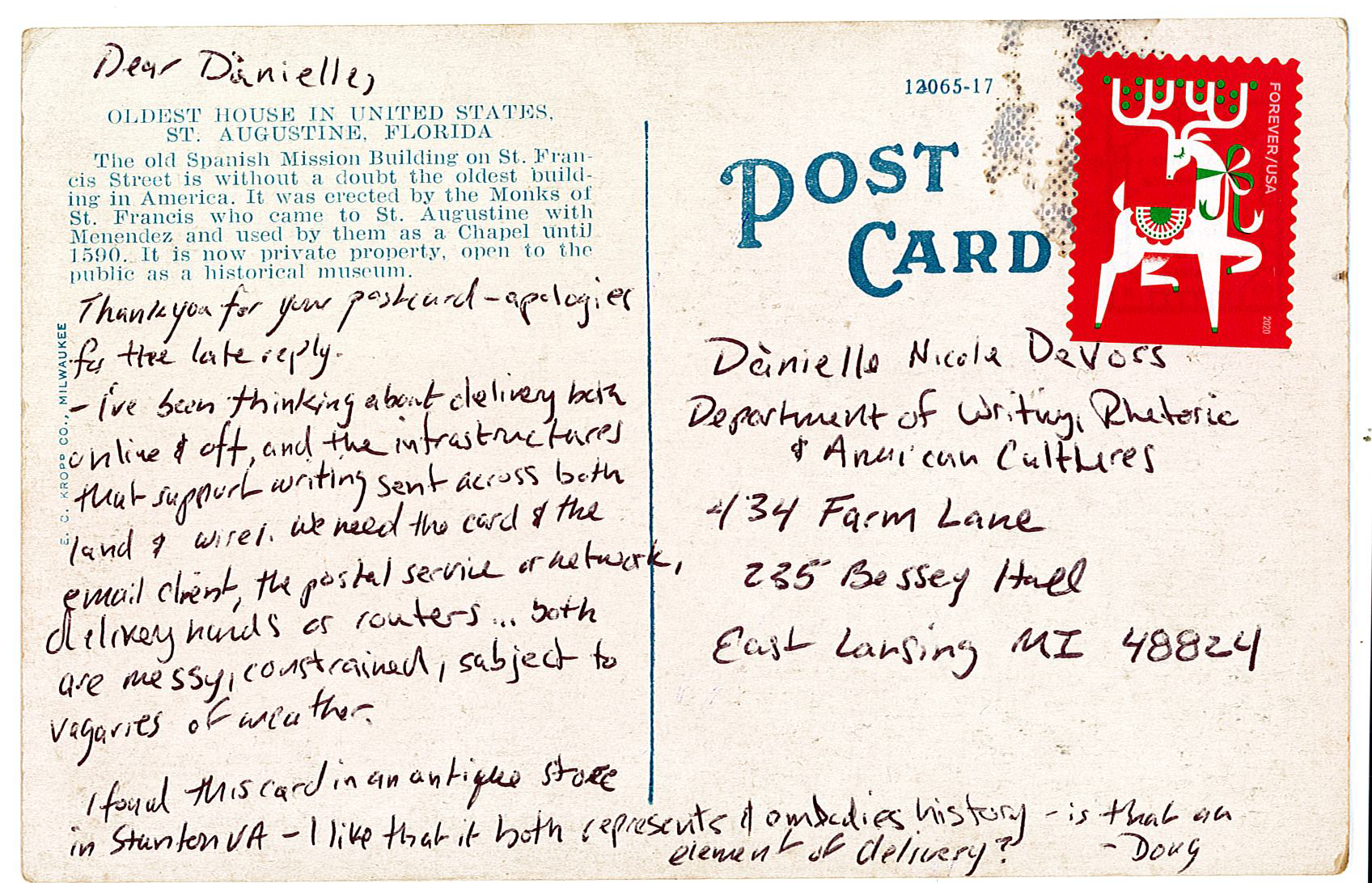

Doug noted that he had to actually write out the text digitally to edit and revise before committing to indelible ink on paper. He was thankful for having cultivated very small lettering in his handwriting style (see Figure 2), as that worked well to squeeze information into the small scope of the composing space on each card. After writing two cards, his hands were starting to cramp up a bit, highlighting the embodied nature of this kind of writing, which is more recognizable and explicit than typing or texting.

Figure 2: The back of Doug’s first postcard.

The moment of delivery, too, is more obviously embodied—sending our postcards required moving the cards to a post box or post office, where they were physically transported. From Doug in Virginia, to Naomi and Dànielle, situated an hour apart from each other in Michigan. Doug experienced a delay in finding proper postage and in finding time to go to the post office and (particularly in the case of the second postcard) brave the long lines of holiday mailers at the post office. Unlike sending an email, the physicality of the postcard means that its use can also aid the circulation of other, less-desirable communicative messages, like the flu.

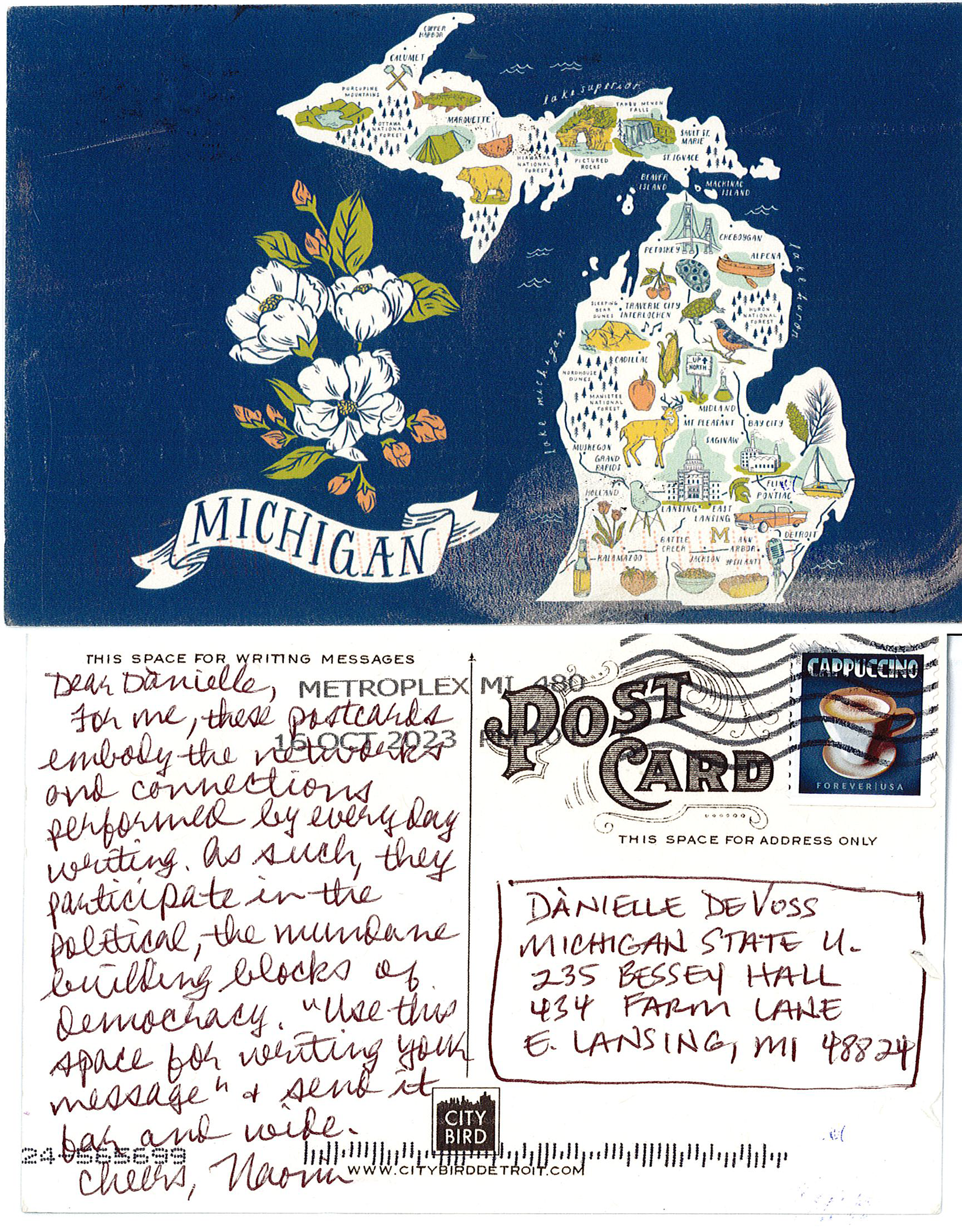

Naomi wrote this prompt to get herself started on the first postcard (see Figure 3):

Prompt for Postcard 1: Reflecting on what we’re doing. What am I doing? Creating connection, reflecting on postcards as a means of delivery of everyday writing, reflecting on everyday writing as an aspect of political speech in a democracy.

I’m realizing that the two Michigan mitten postcards I bought for this first round are quite small with not very much room for writing. I’m not sure that’s good…

On the backs of the postcards: “This space for writing messages,” “This space for address only.” Interesting imperatives, a kind of bureaucratic text, procedural rhetoric, classification. Faux old-fashioned or vintage look (or maybe a reproduction of an actual old card design). From City Bird in Detroit (citybirddetroit.com), on Canfield (though purchased at Schuler Books in Ann Arbor).

Figure 3: The front and back of Naomi’s first postcard.

Dànielle did not draft her postcard text via computer, but after writing the cards to Doug and Naomi reflected in a Google doc:

I honestly can’t remember the last time I was so hesitant to write. The act of committing ink to page—or, rather, to the thick slightly glossy paper of the postcard—threw me. I also can’t remember the last time I handwrote anything. For anyone.

I email. I text. I post. These compositions almost always have immediacy.

Please get cream cheese at the store.

Please submit your syllabi to our department archive using the form link below by 5pm on Friday, September 29.

This Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) serves to document the expectations that will guide your work in the department in the coming academic semester.

Class plans for today: 1. Review the class agenda; 2. Discuss questions people may have about the first project; 3. Do the first reading activity.

I wrote the first two sentences on the first postcard and my hand immediately began to ache. My wrists have acclimated to the keyboard. My fingers know how to seek out keys without me needing to look down. I can type 120 words a minute with minimal errors. By the third sentence, I had to stop writing and shake my hand loose.

I don’t even write grocery lists.

***

When we met to read our second postcards to one another, we spent time with the postcards—holding these analog objects up to our webcams, describing what we saw on each.

Each of us also physically—and viscerally—experienced the physical limitations (invitation?) of the postcard. It was a jarring move from our typical writing in digital spaces where “space” and “page” are seemingly limitless even if page margins are marked on a screen and meant to remind us of the 8” x 11” landscape in which we typically compose. Much of the physical real estate of the 4” by 6” or so cards were occupied by explanatory text and room reserved for addressing and stamping, and the entire front of each postcard devoted entirely to a photo, image, drawing, map, etc.

When Dànielle began writing her first postcards, she narrated in her reflection:

I realize I haven’t yet really explored the postcard itself other than the photo on the front and the blank, left side space on the back. There’s no title. There’s no explanatory text. There’s no name for the place.

There’s a small PRINTED WITH SOY INK textbox, with a graphic of a red and blue and white flag inside a droplet outline. The green-arrows recycling graphic appears next to it.

msu.edu is centered at the bottom of the postcard, and under it reads PHOTOS BY W. SALVATI. PRODUCED BY ©2019 PHOTOGRAFX WORLDWIDE LLC 1.877.285.5766 * PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. WITH RECYCLED PAPER & SOY INKS

This text is in perhaps 7 point font and ALL CAPS. I have to put on my readers and I still strain to read it. There is no magnify option.

The image on the front of the postcard is of the Children’s Gardens on campus. I know this because I’ve been there many times. It’s clearly mid-to-late summer and the gardens are full. Flowers are blooming. Vines are creeping. Trees are lush with green leaves.

No one is in the garden. The photo is taken at the entrance, looking into the gardens. The garden playhouse is to the right, but the small seating area in front of it is obscured by tall plants. The wood fence in the far back of the gardens blocks the view of the road on the other side of the gardens, and the sprawling large animal vet med clinic across the street.

I know in the garden there are two small ponds. At one of the ponds is a fountain where if you swing a small metal gate as hard and fast as you can, a stone frog will spit water toward you. There are herbs throughout the garden, and usually three or four types of basil. I can never resist pulling leaves and then tearing them to inhale the green smell.

Doug noted that

So much of my vernacular writing these days is online—notes to myself, to-do lists, emails short and otherwise. The postcard experience reminded me quite a bit of writing email—I always write and re-write and then edit even the simplest of emails, pondering: Did I get the tone right for this recipient or these receivers? Did I include a joke, a sarcastic comment that I can't be certain won't fall flat or be unrecognized as such? What's the best signoff? I was thinking in the same ways when writing the postcard, but there was an added pressure of knowing that the text on the card would be, to some extent, very public—any hands it passed through could be readers' hands. So perhaps it's more like a Facebook post, although I put less care into those than I do into email… or into postcard writing even though I know those online posts are in fact much more open to the public. The shortness of the message also reminded me of the back-and-forth of the short missives in Spooner and Yancey's (1996) "Notes on a Genre of Email"—you could get a similar effect with many postcards, but much slower.

And of course that article is itself an analog representation of digital communication (we only had paper copies of College Composition and Communication then, mailed to our home or institutional addresses, or retrieved from the library to be read there or photocopied and carried along with us) and the way we are writing and then digitizing postcards in a webtext is the converse of that example.

***

Students also noted that at least some of these everyday texts seemed anachronistic if not foreign to them: three students, for instance, had never written a postcard and didn’t know how to “write” it (e.g., where to put the recipient’s address or at what angle) (Yancey, 2020b, p. 149, "The Museum of Everyday Writing").

Postcards are a genre. A type of writing. A type of writing whose delivery isn’t digitally mediated (at least not on the surface; postcards are, of course, part of larger digital systems today—of UPC codes and postal scanning and routing). The “digits” mediated by this type of composing are our fingers (drawing from Angela Haas, 2007). The space of this writing certainly isn’t infinite. This writing doesn't happen on or across screens. The spread of this writing isn’t rhizomatic or multichannel. We spent a good deal of time discussing the rhetorical contexts and genre conventions of postcards.

Related to the embodied experience of working within the constraints of a small physical writing space, Dànielle reflected feeling “the postcardness of the card calling me to perform in certain writerly ways.” She turned to ChatGPT to generate text for a postcard. A lazy prompt writer, she input the following prompt: Write text for a postcard. ChatGPT produced “Wish you were here to witness the breathtaking beauty of Paradise Cove!”

She noted feeling obligated by this genre and this template to think and write about travel and space. ChatGPT certainly has.

Everyday writing often evokes images of very personal writing—diaries, calendars, and to-do lists come to mind—but many of the texts of everyday writing contribute to a social ecology, either as context for their circulation or as a function of deliberation. (Yancey, 2020a, p. 5)

Everyday writing plays roles both mundane and consequential. (Yancey, 2020a, p. 2)

Everyday writing happens in the moment, in and across the every day, and can create connections in that present—with family, with friends, in public spaces (the comment feed responding to a local newspaper article, for instance), and across networks. Postcards create networks; postcards act as nodes in networks.

Doug was hard-pressed to see the postcard writing as "everyday writing," as it has been years since he wrote one (certainly not days), but he could identify it as Yancey would describe it: "vernacular" writing, much like a scrapbook, a personal journal, or a family history (see Davis & Yancey, 2014).

Naomi wrote on the postcards: “For me, these postcards embody the networks and connections performed by everyday writing. As such, they participate in the political, the mundane building blocks of democracy. ‘Use this space for writing your message,’ and send it far and wide.”

[VIDEO FROM INTERVIEW: Kathi talking about sending texts for campaigns]

Naomi described her most recent experience with postcards in similar terms:

My most recent experience with postcards was part of canvassing during the 2020 election, writing postcards on behalf of some organization to inconsistent Democratic voters in Georgia to tell them about why I think voting is important and urging them to vote in the Senate race for Ossoff and Warnock. I wrote out my script in advance, with 3 or 4 different reasons that were important to me, and then I copied that script onto the postcards, using the different reasons on different cards. I wrote pretty small and filled the whole card. (I’ll probably do something similar for this project - write out what I want to say in advance and then copy it onto the card… That way, I won’t waste space by ‘messing up’ and I’ll be able to develop my ideas a bit more.)

***

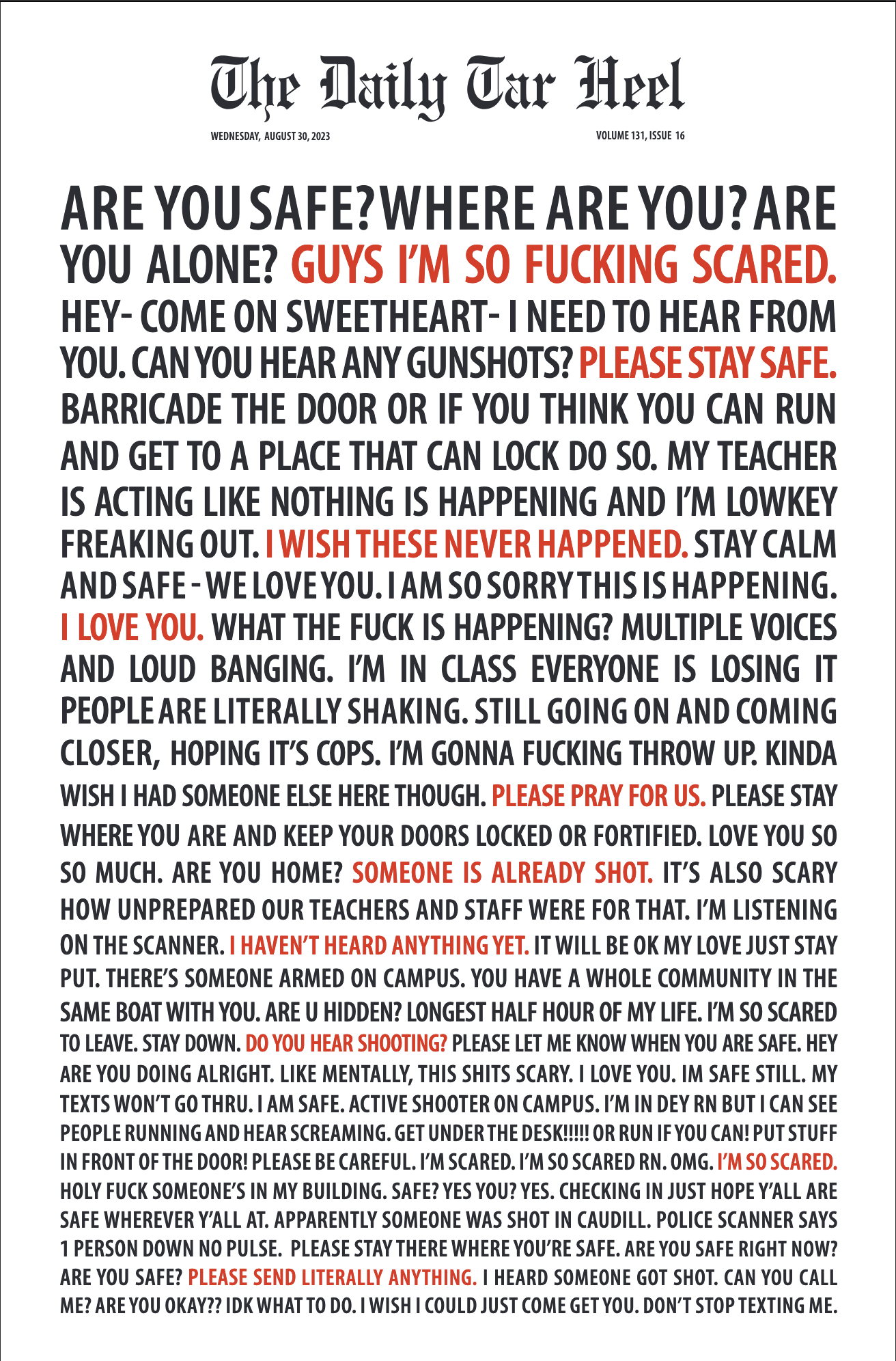

We don’t quite remember who mentioned it, but in our meandering brainstorm the first week of September, someone mentioned the front page of the UNC Chapel Hill school newspaper on August 30, 2023, the day after an active shooter left one professor dead. The day after the shooting, the campus newspaper filled their front page with texts sent during the 3 hour and 10 minute campus lockdown.

Link to issue: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1o-EFSJYcK36e-yXptkpN4O_VBIbNBYb3/view?usp=drive_link

In the interview on delivery with the editors of this collection, Yancey is asked “what aspects of delivery do you think are currently under researched and under theorized or simply warrant more attention?” Yancey’s response is “how everyday people use delivery to accomplish their ends. So one example would be Parkland. The Parkland people.” She said that they “used every means of delivery you can think of…” They marched. They circulated a tag across social media. They initiated and championed legislation. They led campaigns to fund raise, and raised more than $7.5 million for victims. They wrote a book.

Parkland. UNC. The cover of the UNC campus newspaper. In that brainstorming meeting, each of us opened it on our browsers and sat in Zoom, silently reading and absorbing the front page. We talked about delivery in this context—a context of fear. A context of the unknown. A context of ephemeral, quick snippets typically lost or forgotten on individual screens but here captured, designed, and displayed in a wall of texts. We talked about how powerful and potent this transmediation, remediation was and the ways in which delivery shifted as these snippets moved from individual screens to a collage, from quick-sent scrolling moments to this fixed display.

***

In “Notebooks, Annotations, and Tweets: Defining Everyday Writing through a Common Lens,” Yancey and her co-authors mention the example of a child drawing in chalk on the sidewalk, and this reminded Naomi of the On the Media (2023) episode she recently heard, part 3 of the series they’re calling “We Don’t Talk About Leonard,” which focuses on the Republican operative Leonard Leo. In this episode, protesters outside his house in Maine chalk the sidewalk with messages protesting his actions in helping to stack state and regional courts and the decisions that have come down from Republican majority courts as a result. One protester describes Leo later walking down the street and adding the names of the protesters in chalk next to their messages—presumably as a way of doxxing and trolling them? This protester encountered him writing her name while she was out for her morning jog and expressed her sense of weirdness that a multi-millionaire like himself would be out doing that. Leo then described that he later washed away the names he wrote because he thought his actions were undignified (or something to that effect). This is weird and consequential everyday writing. It is part and parcel of our democratic forms of interaction, dialogue, protest, fighting. It is low-tech and low-cost. It is available to “regular” townspeople and elite residents alike. It leaves a public record, but it is also ephemeral, able to be removed, washed away.

As we worked on this chapter, we discussed seeking out specific types of postcards, ideally postcards marking a moment in time, a place in space, a happening (not necessarily a happenstance). When we started thinking about finding an existing postcard (rather than writing one) to use as a touchstone for our thoughts on the genre conventions and uses of postcards as vernacular texts, Doug recalled two related major Internet phenomena: Reddit's r/foundpaper, where users post images of messages found with as much context as they can glean, and Frank Warren's postsecret.com, where anonymous senders mail postcards with secrets on them, some of which are selected for weekly exhibits on the website. We also spoke about the ephemerality of digital messages versus those on postcards (which, being physical, may last longer, but can also easily be lost or misplaced). This sense of ephemerality hit home for Doug when he found a link to Martin Parr's collection of “Boring Postcards,” but the site no longer exists. Parr began collecting and publishing curations of “boring postcards” in Britain in the 1960s. He published a U.S. collection in 2004. Figure 4 is just one of the many “boring” postcards that appears in the book. We are unsure whether the site was part of his U.S.-based collecting and curating in the early 2000s or the site existed before he turned to the U.S.—another fascinating moment across the analog and the digital.

Figure 4: Picturesque Indiana from Boring Postcards (Parr, YEAR).

The place where Danielle had most often seen postcards were antique shops. There are several massive antique “malls” in the Lansing area, one north of town, just off I-69. The “Lansing Mega Mall” occupies a massive one-story building, and has been split into dozens of aisles with hundreds of individual stalls. Most of the stallkeepers invest extensive time and energy into arranging their stalls and the antiques for sale in them. Danielle found her third postcard example in a whimsically designed stall that featured salvaged farmhouse furniture and goods—antique egg-collecting baskets, an ancient ice chest, a range of old kitchen items, most rusty metal or heavily nicked and worn wood. There was a glass-topped small display case in the front of the stall and on top of the case was a stack of postcards. The postcards were presented in three-hole punched, office-paper sized plastic sheets, with four postcards displayed in each sheet. The stallkeeper had clearly selected and arranged the postcards thematically. The sleeve Danielle chose had four Thanksgiving-themed postcards displayed in it.

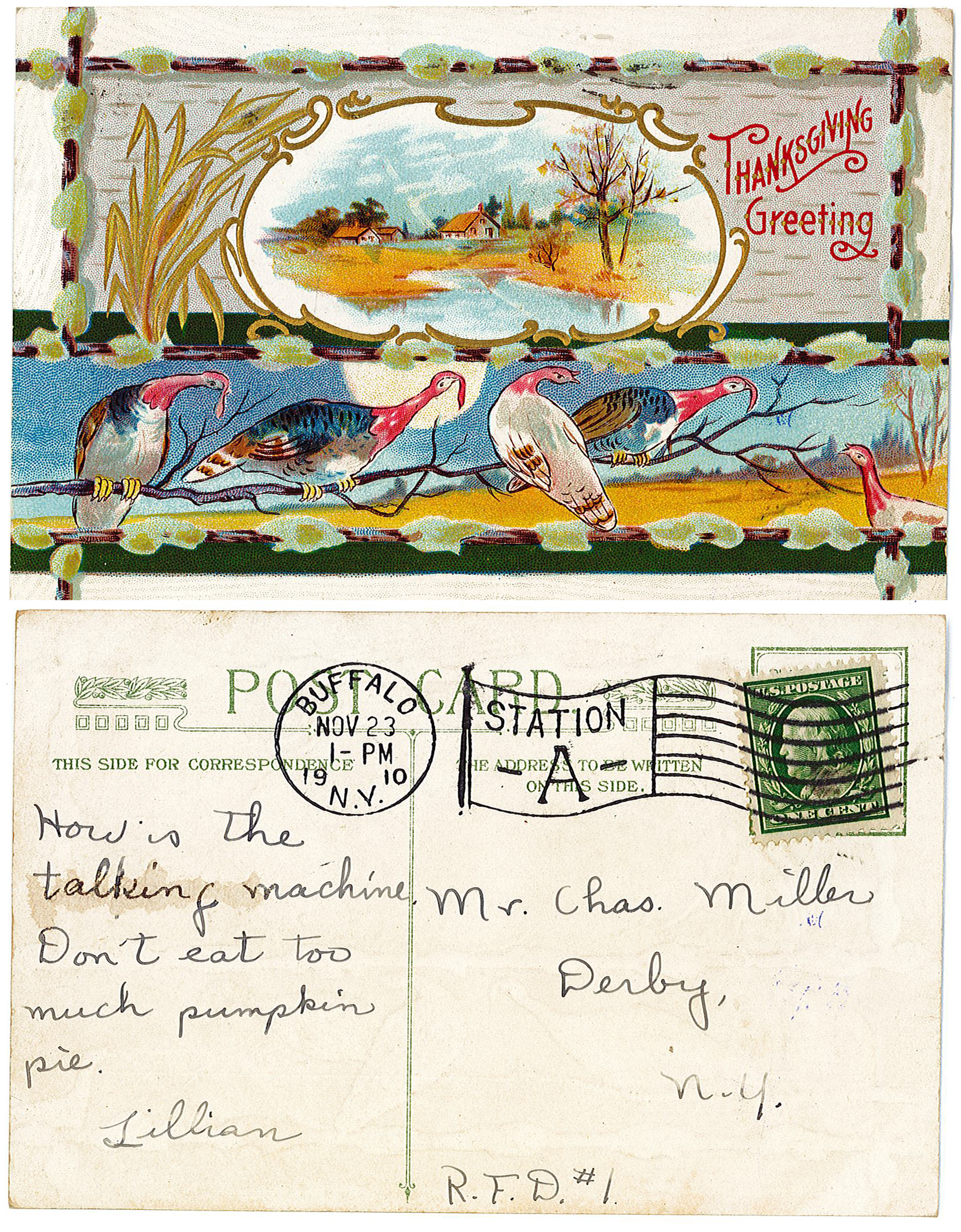

The postcard that gave Danielle pause was one that featured four colorful turkeys on the front, painted in watercolor with “Thanksgiving Greeting” in red, hand-lettered script text. The poststamp reads BUFFALO NOV 23 1-PM 1910 N.Y., with a STATION A stamp next to it. The text, cursive and lettered in pencil, reads “How is the talking machine. Don’t eat too much pumpkin pie. Lillian” The addressee is “Mr. Chas. Miller; Derby, N.Y.” This postcard is jarring and delightful as a particularly exciting moment in time—a person handwriting and physically mailing a card to inquire about the recipient’s telephone (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Front and back of found postcard.

Certainly it captures a moment of technological transition. Of the migration and evolution of the everyday from written card to real-time telephony. From handwriting to voice speaking. From material object delivered by machine and hand to ephemeral sound traveling across wires and tubes.

We want to end here—but not end here, of course, as Yancey’s work will continue to circulate, to deliver, to be delivered—with a snippet of what emerged in our conversation as we worked on this chapter: Doug said, "my goal and to some extent my assumption is that we use our tools of rhetoric to do good in the world, right? To promote good methods. To circulate to the right audience, the right time, the right message…” and Danielle asked, “isn't that one of the responsibilities of rhetoric that we have to carry?"

Davis, Matthew, & Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2014). Notes toward the role of materiality in composing, reviewing, and assessing multimodal texts. Computers and Composition, 31, 13-28.

Haas, Angela M. (2007). Wampum as hypertext: An American Indian intellectual tradition of multimedia theory and practice. Studies in American Indian Literature, 19 (4), 77-100.

Hesse, Doug; Sommers, Nancy; & Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2012). Evocative objects: Reflections on teaching, learning, and living in between. College English, 74(4), 325-350.

McElroy, Stephen J. (2017). Assemblages of Asbury Park: The persistent legacy of the large-letter postcard. In Kathleen Blake Yancey & Stephen J. McElroy (Eds.), Assembling composition (pp. 161-185). NCTE: Studies in Writing and Rhetoric.

On the Media. (2023). We Don't Talk About Leonard, Episodes 1, 2, and 3. https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/otm /episodes/on-the-media-we-dont-talk-about-leonard-episode-1

Parr, Martin. (2004). Boring postcards. Phaidon Press.

Spooner, Michael, & Yancey, Kathleen. (1996). Postings on a genre of email. College Composition and Communication, 47 (2), 252-278.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2004). Made not only in words: Composition in a new key. College Composition and Communication, 56 (2), 297-328.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2004, March). Made not only in words: Composition in a new key. Conference chair’s address at the Conference on College Composition and Communication, San Antonio, TX.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (Ed.). (2006). Delivering college composition: The fifth canon. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann/ BoyntonCook.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2015). Cultures, contexts, images, and texts: Materials for a new age of meaning-making. South Atlantic Review, 80 (3-4), 1-12.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2016). Print, digital, and the liminal counterpart (in-between): The lessons of Hill's Manual of Social and Business Forms for rhetorical delivery. enculturation: https://www.enculturation.net/print-digital-and-the-liminal-counterpart

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2020a). Everyday writing: An introduction. South Atlantic Review, 85 (2), 1-6.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2020b). The Museum of Everyday Writing: Exhibits of everyday writing articulating the past, representing the present, and anticipating the future. South Atlantic Review, 85 (2), 146-166.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake ; Cirio, Joe; Naftzinger, Jeff; & Workman, Erin. (2020). Notebooks, annotations, and Tweets: Defining everyday writing through a common lens. South Atlantic Review, 85 (2), 7-34.