In Fall 2023, I participated in three events related to journal editing and publishing: 1) a roundtable on journals in the field for the Council of Programs in Scientific and Technical Communication; 2) a webinar sponsored by a commercial publishing company about open access publishing; and 3) a dissertation research focus group of editors asked to share mediated practices when the peer review process goes awry. I mention these to highlight the continued importance and concern about the accessibility to and inclusiveness of scholarly knowledge both in the discipline of writing studies and the academy at large, themes that align with questions about genre, modality, meaning and knowledge-making and the mediating role journal editing plays.

These themes have been at the hallmark of Kathleen Blake Yancey’s work for the last four decades. It is important that I acknowledge the consistent role Kathi has played in my own development as a writer and a collaborator, including one of my earliest collaborations with Pam Takayoshi on a chapter on electronic portfolios in Kathi’s co-edited collection, Situating Portfolios: Four Perspectives. Pam and I were fortunate to be mentored by Kathi during her time at Purdue University, our shared alma maters. Little did I know what an impact Kathi would have on my career when I was a graduate student so many years ago as an editorial mentor and role model. Given their status as former students of Kathi’s, this mentoring also extends to the editors of this collection who have gone on to strong careers, along with the numerous others Kathi has engaged in co-authorship and co-editorship that include the award-winning Writing across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing with FSU doctoral alumnae Liane Robertson and Kara Taczak, or her Studies in Writing and Rhetoric collection with Stephen McElroy, Assembling Composition. As an editor and as a leader, Kathi has always had a way of making one feel as if their voice was important, that she was interested in what you had to say, as the original email inviting me to contribute to Assembling Composition indicates:

Dear Kris~~ Attached you'll find an invitation to contribute to an edited collection that Stephen McElroy and I are co-editing on assemblage. In addition, we have attached an overview of the collection to give you a sense of the context and purpose of the volume. If you have questions, please do send them on; given your work on composing, we obviously hope that you'll join this project. Thanks for thinking about this: we look forward to hearing from you.

k

Such missives have typified my professional relationship with Kathi over the years, gracious, collegial invitations to join the conversation. Similarly, as the editor (soon to be outgoing) of Computers and Composition since 2011 and its separate companion web journal Computers and Composition Online since 2002, it has been a true honor to be a contributor to such conversations and provide guidance and mentoring to early-career scholars or to those across the globe less familiar with the journal, but who want to join the dialogue. It’s an even greater honor to be asked by the editors of Kathleen Blake Yancey A to Z: Festschrift in a New Key, and by Kathi herself, to share my perspective with the many other distinguished scholars in this collection about her groundbreaking work as a researcher, administrator, editor, and disciplinary leader throughout her distinguished career. With her editorial oversight of not just one but two journals and 13 edited collections, she is an editor among editors and truly the notable exemplar of our field, something formally recognized by the Conference on College Composition and Communication with its 2018 Exemplar Award.

Yet even with the focus on “J” for journal, the challenge of maintaining this singular focus is daunting, ensuring in this response that Kathi’s contributions to my own growth as a scholar, teacher, and editor are evident and reflective of her powerful impact on the formation of multiple subdisciplines that include assessment and digital writing studies. Equally daunting is the acknowledgment that the emphasis on the journal creates a myriad of connections to other important concepts that impact the possibilities and constraints of scholarly editing, including collaboration, collectives, collegiality, circulation, and communities. These are outcomes of Kathi’s editorial efforts over the years to both provide a space for so many of us to thrive individually and collectively and to be a welcoming force for future voices. Indeed, it seems fitting that the incoming editors of College Composition and Communication are Matthew Davis and Kara Taczak, who served as editorial assistants under Kathi during her term as editor from 2009-2014.

Disciplinary Ideologies

Disciplinary IdeologiesResponding to the role of journals and such collections themselves in circulating disciplinary knowledge, Kathi points to her work with Brian Huot in creating Assessing Writing in 1994, originally published by Ablex and now by Elsevier and which they co-edited for seven years. Yancey contends that the journal’s origin story has much to do with the absence of space specifically devoted to writing assessment, an area of substantial expertise for both scholars, impacting the continuity of conversations focused on assessment and potentially leading to gaps and privileging of some voices among others, a common challenge then and now. Indeed, for Kathi and others, the goal of editorial roles is more than just joining an existing conversation but in creating new ones, a blend of past, present, and future that sustains various sub-disciplines as new voices enter the dialogue in ways that continually shape and reshape the participation in and values of our scholarly discourse communities. Kathi points to the earlier work of Maureen Daly Goggin’s (2000) Inventing a Discipline, and I would include Goggin's (2000) Authoring a Discipline in foregrounding the recursive role of journals, their editors, reviewers, and authors in the field’s history.

Undoubtedly, scholarly publishing and editing are political processes on a number of fronts. What are we allowed to talk about? Whose voices are allowed to speak? How do we question as a discipline who is missing from the conversation? In addressing these questions, James Porter’s (1991) Audience and Rhetoric: An Archaeological Composition of the Discourse Community, specifically his reliance on a Foucauldian “Forum Analysis,” was a major influence in my early scholarship, so much so that when I began teaching a graduate seminar in Scholarly Publishing while at Bowling Green State University, I utilized this heuristic by having doctoral students assess the overall fit of their scholarly work in process for various journals. This analysis focused on the types of topics and keywords, methods and methodologies, format, and scholarly citations to understand the expectations of a community (see Blair, 2019, pp. 171-72). It also addressed the larger concern among early career authors about the numbers of graduate students, non-tenure track faculty or assistant professors welcome to the community, along with the numbers of diverse scholars.

I do believe that this analysis, as was Porter’s intent, helps understand the construction of discourse communities and their disciplinary expectations. It also acknowledges the sheer anxiety-driven nature of scholarly publishing, tied to a presumed gatekeeping process that lets some of us in and keeps others of us out, often through the perception that peer review processes will be agonistic and harmful, something that connects back to that dissertation research focus group I participated in with other editors. Those feelings are real across scholarly generations, based on institutional structures that make many of us believe we are imposters who do not belong, something I remember all too well with every rejection or revise or resubmit I received. This imposter syndrome was compounded by the importance of publications in the academic job market and in our scholarly advancement on the tenure track, "the publish or perish" mantra.

Fortunately, other larger disciplinary processes have evolved to better advocate and educate for more consistently inclusive editorial processes in ways that make scholarly publishing decisions more transparent and demystify the process to alleviate anxiety. For example, the Conference on College Composition and Communication has developed a Statement on Editorial Ethics that addresses “broader emphasis on the various ethical dilemmas that may emerge in scholarly publication given disparities in power due to multiple and often intersecting positionalities, including ethnicity, gender, ability/disability, class and sexuality, but also related to access to resources, theoretical and scholarly orientation, institutional affiliation, and location on an academic career trajectory” (2023, para. 4). Similarly, Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy has developed an "Inclusivity Action Plan" that holds the entire editorial team accountable for anti-racist structures that, as their plan states, “dismisses the capacious view of who can be a scholar-expert, regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender identity, ability, sexual identity, and other identity markers” (Kairos, 2022, para 1) to, as with the CCCCs, promote an intersectional approach to scholarly publishing.

Diverse scholarly methodologies, including computational corpus linguistics, can help us determine “what we really value,” as Bob Broad’s (2002) book title suggests. Although Broad was speaking about writing assessment, the concept applies to our editorial values as well, given the evaluative role inherent to peer review. More recently, studies such as John Gallagher’s et al.’s “Analysis of Seven Writing Studies Journals, 2000-2019 Part II: Data-Driven Identification of Keywords” contend that “establishing keywords via computational methods, such as TF-IDF and collocation, in a corpus can help new and experienced researchers with identifying disciplinary parlances and specific discourses.” This is undoubtedly an important process to a number of disciplines within writing studies as we trace our histories, ideologies, and values, and is, Porter’s forum analysis suggests, powerful in identifying what isn’t addressed, what keywords or topics are absent, and thus require more proactive efforts on the part of editors to include.

Computers and Composition is not exempt from such constructive critique about what how the journal can foreground more intersectional conversations, as Lori Beth De Hertogh, Liz Lane, and Jessica Ouellette conclude in “’Feminist Leanings:’ Tracing Technofeminist and Intersectional Practices and Values in Three Decades of Computers and Composition.” Published as part of the 2019 Computers and Composition Special Issue, De Hertogh et al. rely primarily on a quantitative coding process, their advocacy for a diversity of mixed methods to promote in this case feminist perspectives is compelling. Part of the concern about intersectionality, particularly for an international journal like Computers and Composition, involves attention to multi- and translingual contexts. As a result, the journal has been more intentional about securing a broad array of international editorial board members to better represent the five continents in which the journal is regularly accessed, with board members from countries that include India, Saudi Arabia, Iran, China, Japan, Singapore, Australia, and numerous others, in order to promote and support research in diverse global contexts. My own concern as an editor and computers and writing specialist is that the emphasis on “multimodality” has in some conversations privileged the digital, with less attention in these conversations on the multicultural and multilingual. This aligns with calls for linguistic justice and extending the affordances of multimodality to global language learners as well as on the original calls by the New London Group (1996), whose canonical work on multiliteracies the field has relied upon to advocate for multimodal composing.

As Kathi shares in her interview, part of Assessing Writing’s start-up challenges included support from her home institution at the time, who as she concedes, had concerns about the impact the journal might have on her academic advancement, that somehow journal editing would detract from meeting more traditional criteria for tenure and promotion:

This perception can be a common challenge for current and prospective editors who end up finding that such work is unceremoniously lumped into the category of service rather than scholarship. Because I have had the opportunity to serve as both a Chair and as a Dean, while I also served as a journal editor, I have always objected to this assessment, stressing for myself and for editorial colleagues that journal editing and by extension the work of edited collections (especially in writing studies) represent a significant form of scholarship in the ability to shape and synthesize conversations within the field on both an individual article or chapter basis.

For those of us working within English Departments, this perception is compounded by cultural ecologies and ideologies that privilege the single-authored monograph for tenure and promotion, as Eble, Morse, Sharer, and Banks (2019) determine in their analysis of approximately 75 tenure and promotion documents to “challenge the monograph driven hierarchy of scholarship that has long ruled evaluations of tenure and promotion cases for most of us…that significant, highly valuable advances in research and scholarship develop through, other often collaborative endeavors, including the editing of scholarly collections and journals” (p. 341). This is especially important in the way voices come together and optimally speak to each other and build upon each other to exemplify diverse viewpoints. I also believe that viewing journal editing, not to mention journal reviewing, as “service work” diminishes the intellectual labor of that work, deeming it less than the efforts of authors who rely heavily on editorial and peer reviewer feedback to reshape ideas based on the concerns of a discourse community.

In her 2019 Exemplar speech later published in College Composition and Communication, Kathi speaks about the "cause" of teaching writing and of learning from students about composing. As she notes, "This cause, however, is more than about my teaching; it's about being part of something larger, something that expands and enriches what any one person does, what any single person can do." Kathi connects this cause to the formation of the field and its sustainability through organizations, journals, research, and curricula. Part of that sustainability includes providing a point of entry to such disciplinary collectives, including through open access and by promoting diverse genres, modalities, and perspectives, and philosophy or "cause" informing her work as a scholar, teacher, editor, and administrator as she has led the field in discussing electronic portfolios, writing transfer, remix and assemblage, and reflection, just to name a few.

This includes her editorship of CCCs, where she also led an important taskforce on the Future of CCCs Online, a separate multimodal journal attempted twice in the history of the organization. As a member of that taskforce, due again to Kathi's continual efforts to include me in conversations; through her leadership, our group's work foregrounded the organizational commitment and resources required to sustain an open-access, multimodal forum for digital scholarship co-equal in its rigor and impact to that of the print journal. In hindsight, perhaps it's not so surprising CCCs Online was not sustainable, in part tied to the necessary editorial, technological, and fiscal infrastructure, including support for the editorial team, the technical and server support of the National Council of Teachers of English, and the overall commitment to valuing the work of editors, authors, and reviewers as they collectively promote multimodal and multigenred forms and their impact on scholarly dialogue. As Doug Hesse (2019) contends in his overview of scholarly journals over nearly 40 years, "It's striking that the field doesn't by now have more journals that embrace multimodality…. This may underscore a fundamental conservatism of the discipline" (p. 383). Nevertheless, it is a testament to the power of those collaborations, collectives, and communities I allude to earlier in this response that multimodal journals such as Kairos have maintained a leadership role in circulating disciplinary knowledge and meaning making about digital rhetoric and multimodal pedagogies for last three decades.

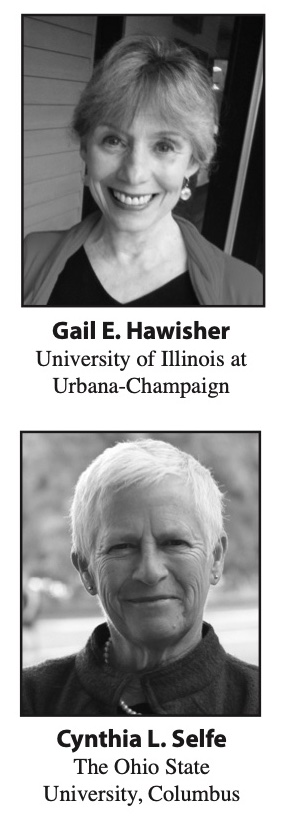

These days, I look for ways to identify disciplinary milestones or anniversaries as an opportunity for reflection. I graduated with a Ph.D. 30 years ago in 1994, and have had the honor of knowing Kathi Yancey for that time. As I now approach retirement, I realize that so much of my work is connected to those who mentored me, who invited me to be part of a community, including in this collection, as Kathi, Stephen, Rory, and Matt have done. In speaking about the origins of Assessing Writing, Kathi also credits Cynthia Selfe and Gail Hawisher, who in founding and editing Computers and Composition provided modeling about how to navigate academic publishing both within a discourse community and with professional publishers, and how the metrics of publication success can be very different between the two.

As award winning exemplars of the field, Cindy and Gail certainly provided that mentoring to me as well, first with the development of Computers and Composition Online and later with Computers and Composition, assuring me that I could take on the editorial leadership of a major journal in the field even when I was certain I could not. Gail Hawisher's death in December 2023 is a tragic loss to the field and to those colleagues, friends, and former students who became frequent collaborators who had the honor of knowing and working with her. As I transition away from this editorial role in January 2025, I encourage us to all reflect upon where we're at, where we want to be, and how we might get there with regard to open access, digital composing, support and reward for scholarly editing and reviewing, and intersectional value systems that further enable diverse pathways rather than the proverbial closed gates that have far too long created anxiety about the academic publishing process. As Heidi McKee (2019) forcefully states "Believe in yourself and in your right--and imperative--to join public and scholarly conversations; believe in the importance of those conversations; and seek the mentors who believe in you" (p. 41).

As award winning exemplars of the field, Cindy and Gail certainly provided that mentoring to me as well, first with the development of Computers and Composition Online and later with Computers and Composition, assuring me that I could take on the editorial leadership of a major journal in the field even when I was certain I could not. Gail Hawisher's death in December 2023 is a tragic loss to the field and to those colleagues, friends, and former students who became frequent collaborators who had the honor of knowing and working with her. As I transition away from this editorial role in January 2025, I encourage us to all reflect upon where we're at, where we want to be, and how we might get there with regard to open access, digital composing, support and reward for scholarly editing and reviewing, and intersectional value systems that further enable diverse pathways rather than the proverbial closed gates that have far too long created anxiety about the academic publishing process. As Heidi McKee (2019) forcefully states "Believe in yourself and in your right--and imperative--to join public and scholarly conversations; believe in the importance of those conversations; and seek the mentors who believe in you" (p. 41).

Despite our collective strides, there is far more work to do among our contemporary discourse communities, especially in our editorial roles within professional and publishing organizations, as well as in our faculty and administrative roles within our home institutions. We must honor Kathi Yancey's similar exemplar role as an advocate and change agent in ways that represent the diversity of the field and the conversations that occur within it. In her message to me about this collection and the passion we have in common for editing, Kathi jokingly asks "what *are* nice girls like us thinking of?" For me the answer is the thought of carrying forward that cause has spoken of from those who mentored us to share with those we have mentored in turn. Thus, we must never forget to acknowledge our mentors and advisors in our disciplinary origin stories and genealogies.

At the end of her interview, Kathi speaks about personal journaling, undoubtedly connected to her important theories of reflection, but just as connected to our collective humanity, especially in crisis times such as the pandemic, and to times when we lose dear mentors such as Gail and several years earlier Janice Lauer, my dissertation advisor and another mentor to many students throughout her exemplary career at Purdue. Kathi points to her Facebook posts "The Things You Learn in a Pandemic," something she has sustained for over three years and that represents her power to reflect on daily life, politics, the larger culture, and our efforts to navigate the world's uncertainties with grace, wit, and laughter, the latter being what Carol Rutz (2010) has characterized as an "irresistible laugh that commands both startled attention and contagious participation" (p. 70):

These posts also represent an experimenting with the genre and purpose of social media, breaking down the relationship between the personal journal and a form of public intellectualism. In note 100, posted on July 16, 2020 at the height of the pandemic, Kathi concludes “I am sorry to be on this journey, but I am so appreciative that you all are taking the journey with me.” I know I am not alone in having immense gratitude that Kathi as a scholar-teacher-administrator-editor-mentor-colleague-friend created spaces for us as she shaped the larger field of writing studies through her powerful work. Through Kathleen Blake Yancey A to Z: Festschrift in a New Key and what is now her 1000th-plus note on Facebook, that shared journey and commitment to collaboration and collectiveness has been one she has encouraged so many of us to travel with her and through her example develop new pathways.

Blair, K. (2019). Read the journals, the move the field. In J.R. Gallagher and D.N. DeVoss (Eds.), Explanation points: Publishing in rhetoric and composition (pp. 170-173). Utah State Univ. Press.

Broad, B. (2003). What we really value: Beyond rubrics in teaching and assessing writing. Utah State Univ. Press.

Conference on College Composition and Communication. (2023). Statement on editorial ethics. CCCC Statement.

De Hertogh, L.B., Lane, L., Ouellette, J. (2019. “Feminist leanings:” Tracing technofeminist and intersectional practices and values in three decades of Computers and Composition. Computers and Composition, 51, 4-13.

DeVoss, D., Haas, A., & Rhodes, J. (2019). Technofeminism: (Re)Generations and intersectional futures. Computers and Composition Special Issue, 51, 1-78.

Eble, M., Morse, T.M., Sharer, W., & Banks, W. (2019). Valuing editorial collaborations as scholarship: A survey of tenure and promotion documents. College English 81(4), 339-366.

Gallagher, J., Wang, H., Modaff, M., Liu, J., & Xu, Y. (2023). Analyses of seven writing studies journals, 2000–2019, Part II: Data-driven identification of keywords. Computers and Composition, 67.Goggin, M.D. (2000). Authoring a discipline: Scholarly journals and the post-World War emergence of rhetoric and composition. Routledge.

Hesse, D. (2019). Journals in composition studies, 35 years after. College English, 81(4), 367-396.

Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology and Pedagogy. (2022, April). Inclusivity action plan. https://praxis.technorhetoric.net/tiki-index.php?page=PraxisWiki%3A_%3AInclusivity+Action+Plan

McElroy, S. (2023, Aug. 1). Yancey: A to Z project update. Private email.

McKee, H. (2019). Believe in yourself and in your ability to join public and scholarly conversations. In J.R. Gallagher and D.N. DeVoss (Eds.), Explanation points: Publishing in rhetoric and composition (pp. 41-44). Utah State Univ. Press.

New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66, 60-92.

Porter, J.E. (1991). Audience and rhetoric: An archaeological composition of the discourse community. Pearson.

Rutz, C. (2010). Making a difference through serendipity and skill: An interview with Kathleen Blake Yancey. WAC Journal, 21, 69-75.

Yancey, K.B., & Weiser, I. (Eds.) (1997). Situating portfolios: Four perspectives. Utah State Univ. Press.

Yancey, K.B., Robertson, L., & Taczak, K. (2014). Writing across contexts: Transfer, composition, and sites of writing. Utah State Univ. Press.

Yancey, K.B., & McElroy, S. (Eds). (2017). Assembling Composition. NCTE.

Yancey, K.B. (2019). 2018 CCCC Exemplar Award acceptance speech. College Composition and Communication, 71(1), 159-163.

Yancey, K.B. (2013, Nov 3.). An invitation. Private email.

Yancey, K.B.(2020). Notes on a Pandemic: #100. Facebook post.

Yancey, K.B. (2023). J for journal. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COZFurm3xuc&t=190s